Note: this will all sound so much better —as would anything— if you imagine it read in Welles’ mellifluous, autumnal voice:

A century ago this very day, in Kenosha, Wisonsin, a mewling, puking infant was born to Richard and Beatrice Welles, and was named Orson, after his grandfather. Little Orson couldn’t know it yet, but the next 70 years would see him live an astonishing life, criss-crossing continents, living high and low, skittering across theater stages and film sets, intoning into microphones and megaphones, accruing laurels and loathing, dining with kings and duelling with fickle financiers, falling in love and fathering children, ever buffeted by the fair and foul winds of fortune but steering head-on into them, lashed to the mast of his immense self-confidence. Welles is a towering figure in cinema, and yet cinema was just a sliver of his life’s work. But little Orson couldn’t know that yet.

It is hard to imagine Orson Welles as a child —naive, seeking approbation from anyone or anything but his own ferocious intelligence. But indeed he had a childhood, like we all did. Except not like we all did —his was a crazy picaresque, as his alcoholic father, who’d made his fortune inventing a bicycle lamp, took on all the parenting following his musician mother’s death when he was nine. Orson, who was already friends with the children of the Aga Khan, went with his father to Jamaica and to Asia and returned to live in the Illinois hotel they owned. Which then burned down (of course it did), and so he moved on again, attending several different schools (where he established his reputation as an incorrigible kleptomaniac), before his father also died young, when Orson was just 15, stipulating in his will that his son be allowed to choose his own guardian. Just a few years later, snubbing the scholarship Harvard offered him in favor of a European tour, Welles would seemingly on a whim march into Dublin’s Gate Theatre and finagle his way into the company by claiming to be a Broadway star. Apparently, no one bought the lie, but his barefaced charisma in telling it was all the audition he needed.

From acting in theater in Ireland and then the US, to directing plays in New York, to establishing a lucrative career in radio thanks to his glorious speaking voice, to combining all those skills into writing, directing and performing immensely popular and successful radio plays, Welles had established himself as a blazing star long before he ever walked onto a film set. When he finally did start filming for the first time after negotiating an unprecedented Hollywood deal to co-write, direct and star in “Citizen Kane,” he was 25 years and one month old.

We write all this biography partly because it is a lot of fun, but also because 30 years after his death, it’s easy to assume that Welles’ immense legacy is at least partially a fallacy, a product of Hollywood mythmaking when the truth was probably much more banal. But nothing about Welles was banal —even his famous tantrum about that Birds Eye peas commercial may be petty and pathetic, but it’s also weirdly magnificent. And if his stentorian, authoritarian reputation as the original auteur feels creakily unfashionable now in these days when “anyone can direct a movie,” it says less about him than it does about a perverse desire to knock a reputation off its plinth and to enact the kind of cultural parricide our current “democratized” discourse demands.

In fact, modern culture being what it is, even “Citizen Kane,” for so long the go-to title for “greatest film ever made,” has recently fallen victim to this kind of reverse-snobbery. Wrong-headed though it obviously is, there seems to be a growing school of (lack of) thought dedicated to propagating the idea that ‘Kane’ is in fact not “all that” and accepting it as an inarguable fact of the cinephile landscape is a tragically herd-minded approach, against which these courageous iconoclastic renegades are our only bulwark. It’s utter bullshit: admiration for Welles has nothing to do with unquestioning, uncritical acceptance of a handed-down monolithic assessment and everything to do with actually watching his films.

So that’s what we’ve decided to do, to mark this centennial —watch Welles’ films. Or rewatch them (all the directorial features, at least), which is all it takes to buff away whatever dullness they may have acquired in the intervening years and to have Welles’ genius reborn in those dazzling images, those mighty performances, this huge, pure cinema.

“Citizen Kane” (1941)

“Citizen Kane” (1941)

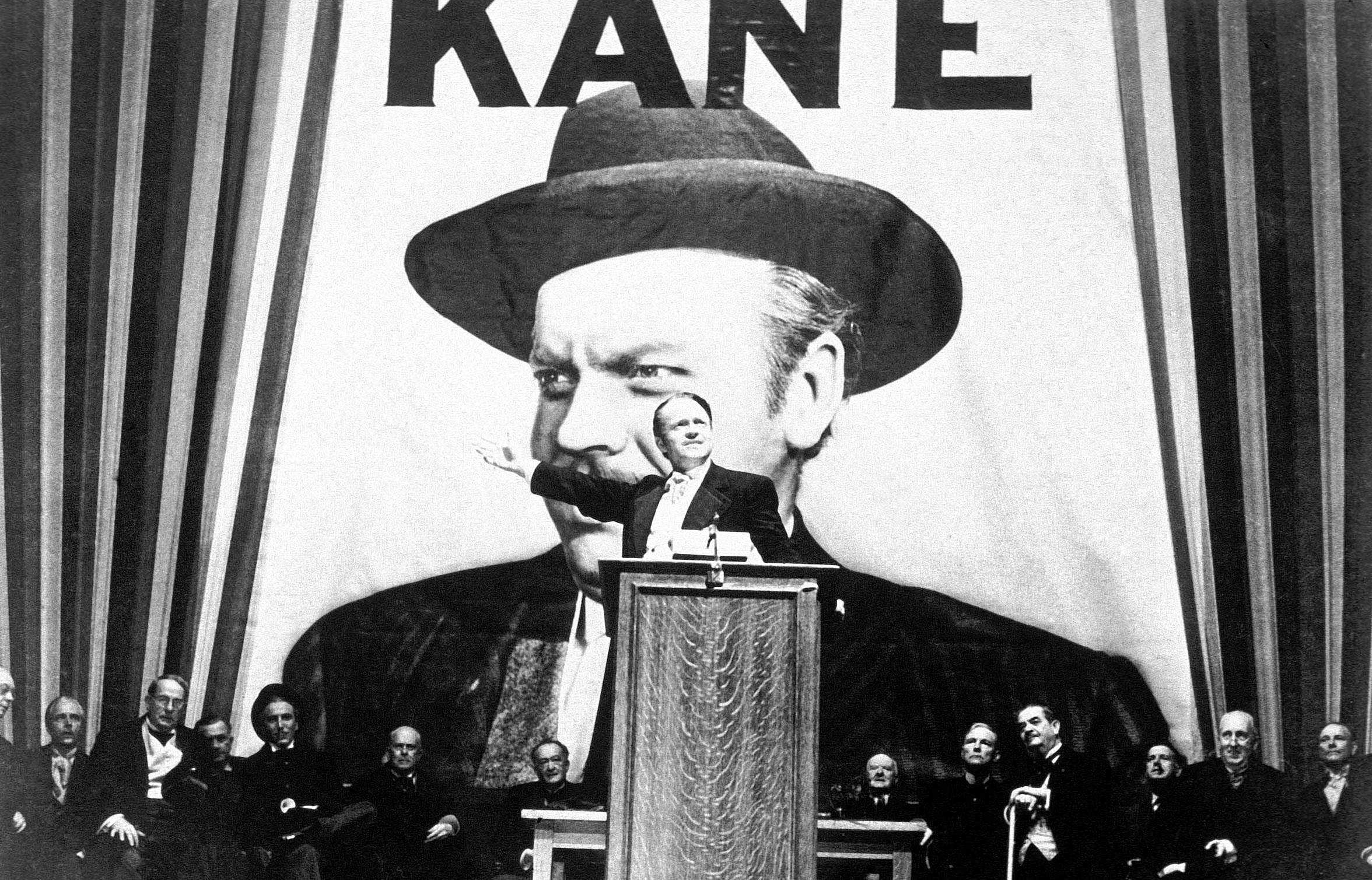

There’s no bigger bang in the history of American cinema than the one created by Orson Welles in 1941, when at the age of 26 he quantified his boy genius status to such a degree that it almost ruined him. The story of how “Citizen Kane” was made, and the colossal shitstorm it caused in Hollywood is as famous as the film itself. The contract that Hollywood offered Welles lit a dynamite stick in his artistic arsenal and led to the greatest debut in cinema, detailing the story of the rise and fall of Charles Foster Kane (Welles) as newspaper tycoon, failed senator, and stupidly-rich hermit who ends his days reminiscing about his carefree childhood. With the benefit of hindsight (and the joys of irony), it’s fitting to note that the posthumous reputation of William Randolph Hearst (the ostensible real ‘Kane’) owes more than a little to Orson Welles and “Citizen Kane,” but at the time, Hearst came dangerously close to making sure the picture never saw the light of day. Everything that surrounds the film has played a part in overexposing it in discussions since, and the embrace of it as the GOAT since the ’60s has slightly suffocated every film Welles made afterwards, but all it takes is one rewatch to see what really matters; the onscreen display of storytelling brilliance that still thrills to this day. Scene after scene, each more technically astounding than the previous, is empowered by Gregg Toland‘s cinematography, Robert Wise‘s editing and the terrific performances Welles got from every cast member (including himself) to create a fluid and meticulously crafted narrative. Telling the story of the soul-corrupting nature of power through its timeless dialogue as much as its unforgettable aesthetic and by framing characters against objects to enhance the materialistic emptiness of an illusionary American dream, “Citizen Kane” is a perennial example of the everlasting artistic power that can be achieved when the camera is in the right hands. [A+]

“The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942)

Almost the archetypal difficult cinematic “second album,” “The Magnificent Ambersons” saw Welles follow up the film often called the greatest ever with a sprawling melodrama, only see backers RKO cut the movie nearly in half and then delete most of the footage. Welles would later say “they destroyed ‘Ambersons,’ and it destroyed me,” but ‘destroyed’ might be a bit harsh, given the inarguable greatness of what still survives. Based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Booth Tarkington, who’d allegedly based the patriarch on Welles’ own father, it’s an ensemble piece about the titular family, the richest in Indianapolis, and the scandal caused by the return of Eugene (Joseph Cotten), a self-made-man in love with Amberson daughter Isabel (Dolores Costello). Somehow less self-consciously showy than ‘Kane’ and more accomplished (the early Christmas ball sequence is an astonishing piece of filmmaking), it is even in subtracted form a dark and uncompromising movie that’s way ahead of its time, at least until the botched ending. Welles doesn’t appear on screen —the only film he directed in which that’s the case— which makes it into a more generous ensemble piece, allowing the actors to truly shine. But he’s still all over the film, not least because he narrates it, and it serves as just as rich a dive into American privilege as its predecessor. It’s unlikely that the missing footage will ever be found, so we’ll always wonder what-if (Robert Wise, who shepherded the cut down version and would later become a great director in his own right, maintains that the released version is as good as the longer one, which tested poorly with audiences), but we’re lucky to have ‘Ambersons’ in any form. [A-]