One year in the life of a teenager can feel like an eternity. The intensity of the fleeting romances, the wild swings between happiness and despair, the thrilling yet uneasy anticipation of a future that seems simultaneously imminent and distant — it’s a wonder that we come out of adolescence intact. But that time shapes who we become, and with her feature debut, Ukrainian filmmaker Kateryna Gornostai chronicles that all-important pre-graduation year, where nothing — and everything — matters. Utilizing non-professional actors, and blurring the lines between documentary and fiction, “Stop-Zemlia” is a sympathetic portrait of the tidal forces of teenagehood. Yet, despite the film’s quiet sprawl and yearning ambition, Gornostai’s painstakingly observant eye never uncovers fresh insight into the thrumming heart of that transformative moment.

READ MORE: The 100 Most Anticipated Films Of 2021

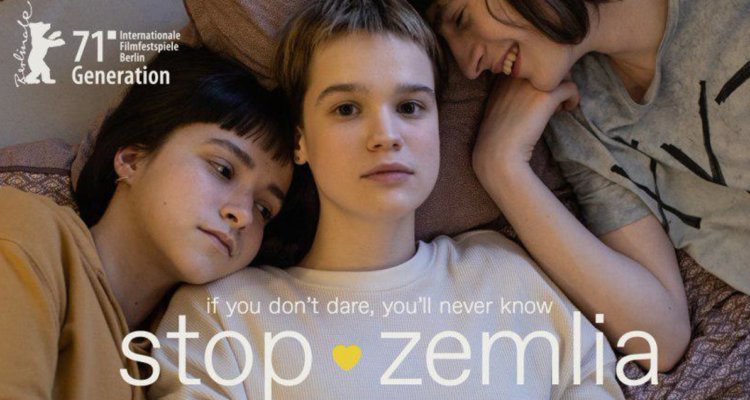

Moving with no particular destination in mind, “Stop-Zemlia” anchors its open-ended narrative around Masha (Maria Fedorchenko). Her concerns are not unlike everyone else at her age: she’s in love, she’s growing mildly concerned about her university entrance exam, and it seems she’s carrying every emotion she’s ever felt on her delicate frame. The uncertainty she feels about herself and the world around her is palpable, but helping her get by are her best friends Yana (Yana Isienko) and Senia (Arsenii Markov), who are so close that they frequently have sleepovers together, sharing Masha’s giant bed. Yet, despite the strength and support she draws from Yana and Senia, Masha is helpless in the face of her attraction to Sasha (Oleksandr Ivanov), whose inability to recognize her feelings, or her indifference to them, might be due to the trouble he has at home with his single mother. Masha also finds her attention diverted by a mysterious admirer on Instagram, with whom she comfortably shares some of her deepest thoughts.

READ MORE: The 25 Best Films Of 2020

Set loosely across the school year, and sometimes muddying the boundaries of past and present, Goronstai crafts a film that aims to be more experiential than expository. The episodic structure freely moves between parties, school trips, dances, and home life, weaving its quartet of main characters into the larger fabric of the student body. This immersiveness is credible and even admirable, but it leaves critical character information often moving by too quickly: depression, PTSD, cutting, bisexuality, abandonment, bullying — these are all issues that the film glides over. Pile on top of that some ultimately extraneous dream sequences and “Stop-Zemlia” is the rare film that, the more it adds, the less meaningful the experience becomes. However, its unhurried meter is nonetheless refreshingly distinct from other teenage dramas which tread on a similar territory in a far more hysterical or hyperactive manner.

Goronstai’s cast, with whom she worked closely to develop their characters, is not only natural in front of the camera, but vulnerable too. Maria Fedorchenko in particular displays a sensitivity that’s undeniably from a personal place not too far below the surface. It’s revealing, then, that the most deeply affecting moment of “Stop-Zemlia” occurs in one of the interviews with the cast members that the director sprinkles throughout the film. Late in the picture, Fedorchenko struggles to formulate a question to Goronstai about whether or not her teenage feelings will follow her into adulthood, before breaking down into tears. The other cast members are also startingly open with Goronstai, to the point that it makes you wonder how much better the results might’ve fared had she turned the acting lab she went through with them into an opportunity to capture their lives in a full-blown, straightforward documentary.

Sadly, however thin the veneer of artifice that Goronstai puts up to create a fictionalized world for her cast and the characters they inhabit, it’s enough to sap “Stop-Zemlia” of its strength. The film’s formlessness, particularly as the two-hour running time drags on, equally suggests a director struggling to find a story, but also genuinely in love with her cast and unable to let anything go. “I just like feeling things, it’s better than feeling nothing,” one of Masha’s classmates says early in the film. You can’t help but think that Goronstai didn’t want the feeling to end either. [C]

You can follow along with the rest of our 2021 Berlin Film Festival coverage here.