Wes Anderson is a genre; one of decorative embellishment, ornamental whimsy, baroque fantasy, and symmetrical precision. It wasn’t always this way, and it’s also not just superficial embroidery. “Rushmore” had a moving bittersweetness anchoring its fanciful formal wit, and “The Royal Tenenbaums” refined Anderson’s patented wistful stories about romantics, failed dreams, and faded glories within imaginative color-coded costumes and increasingly meticulous aesthetics.

READ MORE: 2023 Cannes Film Festival: 21 Must-See Movies To Watch

Somewhere in the middle, the American filmmaker became a little unsure of his identity amidst sudden reproach (‘Life Aquatic,’ ‘Darjeeling Limited’); however, he quickly realized his inimitable cinematic handwriting made him unique. Rebuffing critics, Anderson doubled down on all the hyper-fastidious diorama castigations of preciousness that some charged him with (“Fantastic Mr. Fox”) while managing balance and returning to the poignant elegiacally of his early films (“The Grand Budapest Hotel,” “The French Dispatch”).

READ MORE: Summer 2023 Movie Preview: 52 Must-See Films To Watch

This age of self-awareness is when the Wes Anderson genre fashioned into that unmistakable panache (calcified by pastiche YouTubers and TikTokers mimicking it and doing so poorly). But if “The French Dispatch” was uber-stylized and extravagant in its various dimensions and still achieved depth and emotion—a soulful love letter to journalism, regretful magazine dreams, and the unique loneliness of ex-pat life—then his latest, “Asteroid City,” arguably doesn’t strike the same equilibrium. While mostly pleasant, entertaining, and even occasionally enchanting, “Asteroid City” takes a few steps back into the era when artifice and inventiveness obscured the heart and soul of it all (and someone is going to use the term “Wes Anderson AI” about the overall familiarity of its idiosyncratic élan). Not giant regressive steps, mind you, but enough to notice.

There’s a lot going on in Anderson’s 11th film, arguably too much—even for him. Set in the mid-1950s at a Junior Stargazer convention held in a fictional American desert town (the eponymous “Asteroid City,” think New Mexico meets Nevada), where parents and students all converge for this special annual gathering (so it’s a Santa Fe aesthetic with pastels). The town’s most celebrated attraction is a nearby giant meteoric crater and celestial observatory. Given the multitude of peculiar characters, their various personal dramas and sorrows, and Anderson’s penchant for chock-a-block schematized dialogue, knotty information dumps, and visual density, this would be more than enough for a bountiful Wes Anderson movie.

However, like ‘French Dispatch,’ which jam-packs three short stories within one larger framework (but still resonates in the end), Anderson cannot resist the temptation to layer and lacquer, and he adds a new level of meta-artifice of a play-within-a-play inside his movie. Hidden from view in the marketing (which may be strategic given the extra layer of confusion it may add) is the chorus of it all; a black-and-white prologue and theatrical construction that the film returns to after every few acts (which are all punctiliously indexed-carded on screen, naturally).

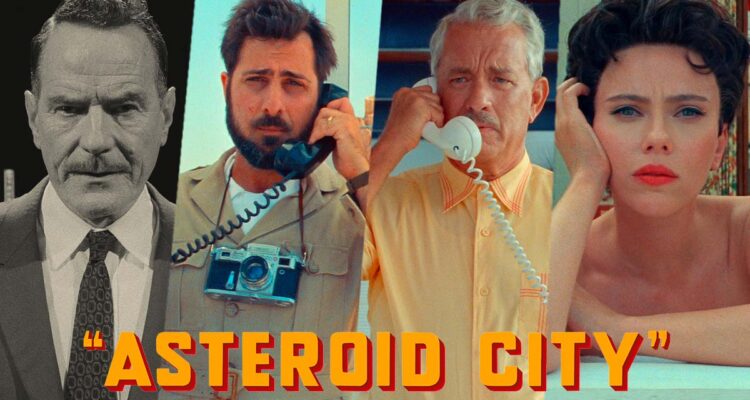

In this opening part of the film, Bryan Cranston plays the narrative host, presenting and explaining who wrote the “Asteroid City” play (Edward Norton), who directs it on the stage (Adrien Brody), and the personal complications of the actors within it (the same actors who star in the “Asteroid City” play within the film—get it?). If it sounds overly fussy, overly complicated, robbing the viewer of a simpler experience and threatening to drown out the empathy and pathos of the desert-set tale, that’s because it is and does. At least to some degree, Anderson seems to miscalculate and overcook his new balance of ingenious creativity with humanity and emotion (though watching Anderson doing ’50s rat-a-tat repartee is admittedly enjoyable).

Not for lack of trying, of course. The would-be heart and soul of “Asteroid City” is the story of a grieving, shattered, but unemotional father (Augie Steenbeck, played by Jason Schwartzman) trying to break the news of his recently-deceased wife to his children, the principal eldest son, Woodrow, played by Jake Ryan (“Moonrise Kingdom”), a dead ringer for an eccentric, young Dustin Hoffman, seemingly destined to be a leading Wes Anderson player one day. Steenbeck crosses paths with the beautiful movie star actress Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johannsson) and her daughter (Grace Edwards), and when a connection is made, something starts to spark between them. Meanwhile, his disapproving father-in-law Stanley Zak (Tom Hanks), who never did like him much, is called in to take care of the children while Augie quietly falls apart inside.

There are a trillion more characters—the best of which are featured in the heartfelt coming-of-age side story featuring Schwartzman and Johannsson’s character’s aforementioned precocious kids, arguably featuring some Amblin-like aspects. There are more families in town for the Stargazer convention (Hope Davis, Liev Schreiber, Sophia Lillis), plus the eccentric locals (Matt Dillon, Steve Carrell, Rupert Friend), scientists (Tilda Swinton), and a military faction too (led by Jeffrey Wright). No part is too small for folks like Jeff Goldblum and Willem Dafoe to appear for 30-odd seconds. But these aspiring inventions and this astronomy convention are spectacularly disrupted by world-changing events (the UFO in the trailer, don’t say spoiler).

Chaos ensues, strict quarantines are placed in effect, and government agents try to lockdown the news of this event before global panic spreads. But all it really does is keep the residents of “Asteroid City” trapped indefinitely. This would be theoretically ideal for the film’s sense of intimacy, but that closeness and the plot’s momentum are derailed constantly by the flash-out, quick-pan returns to black-and-white theatrical scaffolding around the narrative.

And that context, in a way, is a neat trick; watching Scarlett Johannsson on screen, knowing she is an actress playing an actress playing an actress in the movie, but to what end exactly? While “Asteroid City” does reveal what’s really on its mind in the last act, much of this pretense is still distancing, and there’s an argument to be made that Anderson’s making two different movies.

Anderson’s films are often a carefully hand-crafted invitational— both in the immaculately constructed invite itself (embossed lettering, tasteful scribble, all that) and then the larger invitation to experience a new world. And “Asteroid City,” with its moderating presenter and unique period settings, is undoubtedly an invite to enter an alluring new W.A universe. And no one does nostalgic melancholy better than Wes, but it’s almost as if the filmmaker wanted to make a fast-talking New York theater movie (think classic fast-talkin’ ’50s movie like “All About Eve”) but then decided he also wanted to tell a dustier, dolorous tale in the Southwest. And the two aren’t always as congruent as he’d like to think they are.

How does this big, disparate galactic soup of ideas, locations, people, cultures, and milieus come together, if at all? In the reflective notion of loneliness, both in the humanness of the characters and all they lack, and the scale of it when one considers our tiny, insignificant, unknowable place in the universe and the unfathomable mysteries of our lives, but also what’s out there. Why do we create and put such care into our creations like the writers and directors of “Asteroid City,” the play? Perhaps because in the shadow of the vast and frightening cosmos, the unanswerable questions of ‘Why are we here?’ and What does it all mean?’ the act of creation is brave and creates connection, and connection fosters our humanity and togetherness, which makes us all feel less lonely in the galaxy. That’s existentially melancholy stuff— a specific pigment of poignant sadness that Anderson hasn’t pulled out of his neatly-ordered toolkit before. And I’m not overstating the case. However, the minor problem of it all is while what Anderson is trying to say can be read across the sky like a beautifully glistening moonbeam; it does often lack the craterous depth of feeling we know he’s capable of when doing his best creative and emotional astrography. [B]

Follow along with all our coverage from the 2023 Cannes Film Festival.