10. “High Noon” (1952)

10. “High Noon” (1952)

Long before “24” made it its central gimmick with the use of flashy split-screen and a cast of dozens, Fred Zinnemann’s “High Noon” used real-time to never-bettered effect. Gary Cooper, radiating the kind of simple decency he built a career on, gets a defining role as Will Kane, the longtime Marshall of a small New Mexican town. On the verge of giving up this dangerous profession for his pacifist Quaker bride (a never-more-luminous Grace Kelly) he gets word that soulless killer Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), a criminal Kane had brought to justice, has been pardoned on some unexplained technicality. With his beautiful wife tugging him one way and the call of duty sounding from the other direction, Kane chooses to return to the town he’s just left to rally the townsfolk to fight. But Kane, as embodied by Cooper, is a better man than they are, and when they cravenly bolt their doors, he’s left to face peril alone, except for literal eleventh-hour intervention by his wife, who’s given an unusually active role in the climax. And what a climax! One of the classic Western’s best and most paradigmatic showdowns, as the sun sits high overhead, the men face off on a dusty high street and the clock ticks toward twelve…

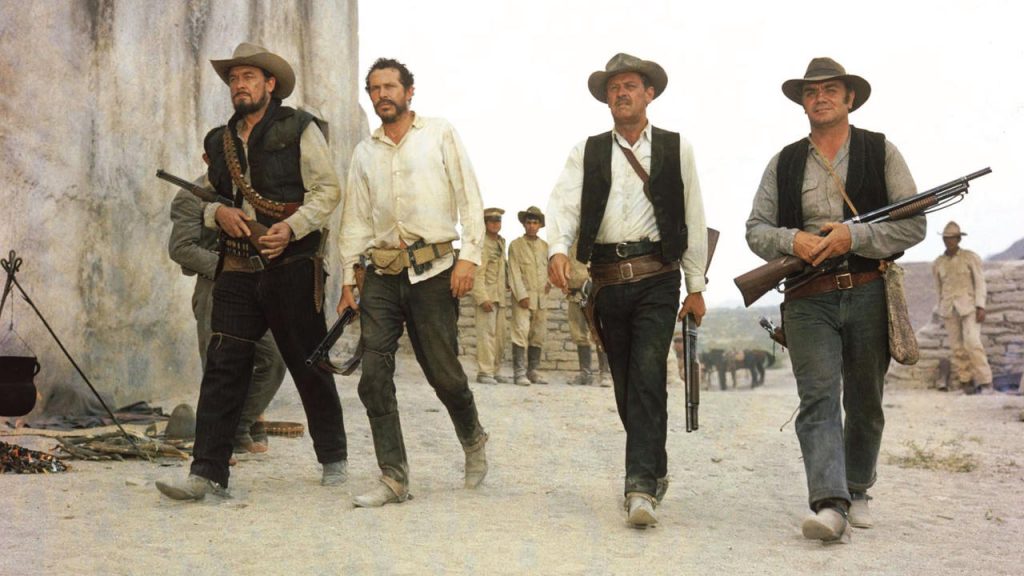

9. “The Wild Bunch” (1969)

9. “The Wild Bunch” (1969)

Non-more-macho director Sam Peckinpah‘s “The Wild Bunch” is widely credited with reinventing the action movie, through the formal innovations that lend its violence such a stylized yet visceral edge. But while its viciousness is the stuff of legend, the overall melancholy tone is striking too. The slender story, set in the dying days of the Old West, as a gang of outlaws led by William Holden are coerced into stealing arms while being pursued by former colleague Robert Ryan and his gang of bounty hunters, was rushed into production in the hopes of beating “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” to the punch. But the famous slo-mo shootouts take more inspiration from “Bonnie & Clyde” than anything more traditionally “Western,” and the supporting players like Ernest Borgnine, Edmond O’Brien, Warren Oates, Ben Johnson and Jaime Sanchez make the quieter moments between the mayhem sing with surprising sensitivity. Peckinpah needed to prove himself, following a rocky patch, and with “The Wild Bunch” his style finally came into alignment with popular opinion: on the cusp of the 1970s Golden Age of Independence, this truculent and abrasive film became the biggest critical and commercial hit of the great director’s career.

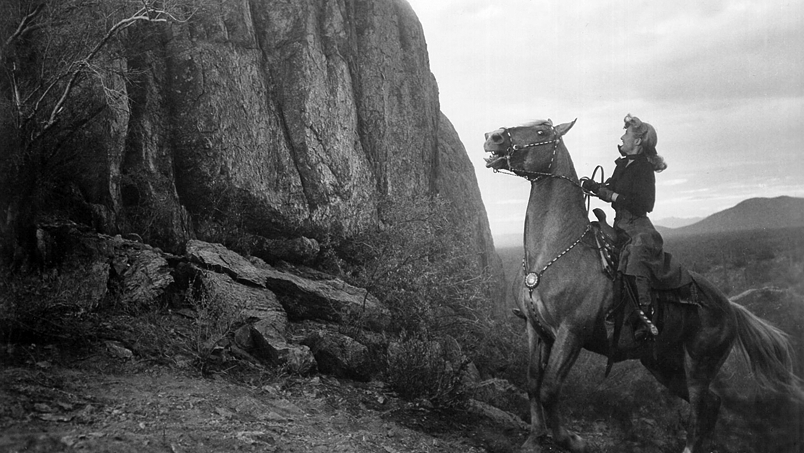

8. “The Furies” (1950)

8. “The Furies” (1950)

It’s truly odd that Anthony Mann is not as well-known a titan of the genre Western as his peers like John Ford. But it’s an even more baffling trick of fate that his best film in the genre is so seldom acknowledged as such. Perhaps it’s because unlike “Winchester ’73” and “The Naked Spur” — see above — and “Bend of the River,” “The Far Country” and “The Man from Laramie” it does not star James Stewart. “The Furies,” Mann’s blistering, scorching Greek tragedy of a movie is still relatively obscure, despite getting the Criterion treatment. An excoriatingly blackhearted and acidic hybrid of Western and women’s picture, it stars the irreplaceable Barbara Stanwyck as the firebrand rancher daughter of a controlling father (Walter Huston, majestic in his final role) whose love-hate relationship with Dad seems borderline incestuous. The searing domestic melodrama (she hates his new fiance, he loathes her boyfriend) is further stoked by a dispute over land, and finally out of spite, the father has her lover hanged, cuing a haughtily contemptuous Stanwyck to embark on a chillingly premediated plan of vengeance. With shades of Dostoyevsky and Shakespeare this is one of the most subversive, oddly kinky Westerns you can find, and it is utterly delicious.

7. “Once Upon A Time In The West” (1968)

7. “Once Upon A Time In The West” (1968)

If you call a movie “Once Upon A Time In The West,” delivering anything but a definitive entry in the genre would have been a let-down. Fortunately, and for all that his Man With No Name trilogy defined the genre, this stone-cold epic is Sergio Leone’s masterpiece. With the backing of a major studio behind him for the first time, and working from a story cooked up by a dream-team of Leone, Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, it marks the clash over a piece of land that a railroad would have to pass through, and the aftermath of the murder of McBain (Frank Wolff) at the hands of sinister gunslinger Frank (Henry Fonda, introduced in a scene that shocks even viewers who didn’t grow up with the actor as the emblem of American goodness), pulling in Harmonica (Charles Bronson), the framed-up bandit Cheyenne (Jason Robards) and the dead man’s widow (Claudia Cardinale). Slower-burning and more sprawling than Leone’s earlier pictures, fiercely political, and stealing from/homaging other movies (including “Johnny Guitar”) in a magpie-ish fashion that makes it as much a commentary on the genre as anything else, it’s a truly remarkable piece of work.

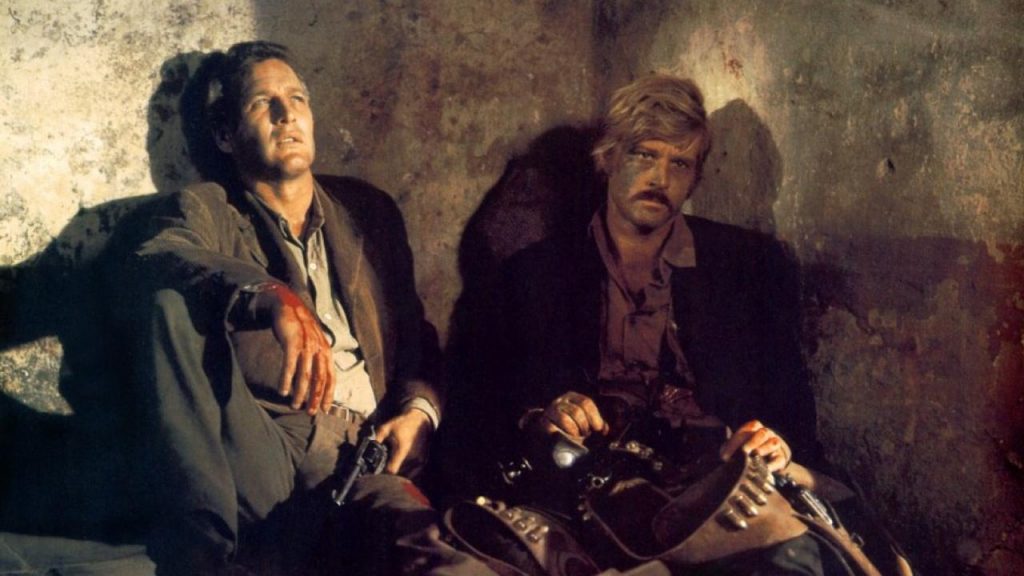

6. “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969)

6. “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969)

There’s a sense that because “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” was such a huge hit, making a megastar of Robert Redford and creating between him and Paul Newman a partership so indelible it’s hard to believe it only spanned two films, George Roy Hill‘s delirious pop-western does not deserve the same serious consideration as, say, a John Ford classic. But let’s not hold its sheer entertainment value against it: written by William Goldman (who won the original screenplay Oscar for it) and explicitly exploring Western mythmaking and legend creation while also contributing to the myth and legend of these real-life outlaws, ‘Butch and Sundance’ is not just frothy fun, it’s exceptionally smart and full-heartedly moving. And of course it’s peppered with unforgettably staged and scored scenes, from Redford pushing Katharine Ross around in a bicycle basket to the tune of “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head,” to that iconic freeze-frame ending that suspends these two (actually quite unsuccessful) bandits at the apex of their frictiony alliance and skewed nobility, and makes sure that that’s how we’ll remember them forever.