There are a few things guaranteed to strike terror into the heart of your average Chicagoan. High on that list would be having your family threatened with a cruel and slow death by a drug cartel, as happens to Jason Bateman in the first episode of his new Netflix culture-clash crime series “Ozark.” Nearly as frightening, and definitely more relatable, is the solution that Bateman’s character improvises to save his family: pack up and move to the Lake of the Ozarks in southern Missouri. Set against relocating to the shores of the artificial lake resort region that one character tartly terms “Redneck Riviera,” there would probably be at least a few Chicagoans who would look at the cartel gunmen and decide, nah, let’s play the odds.

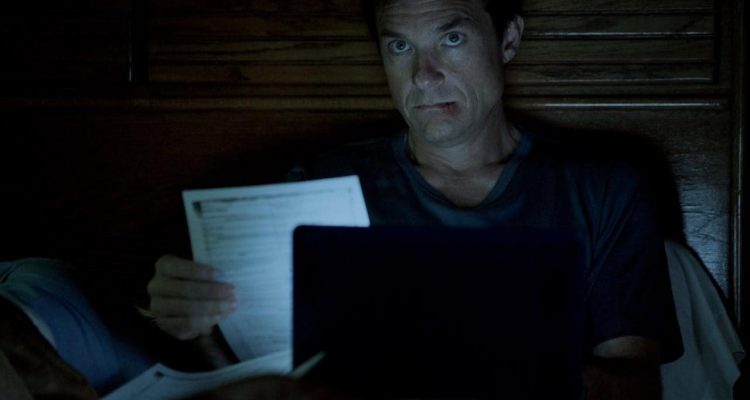

But Marty Byrde (Bateman) isn’t that guy. A financial advisor whose outward demeanor Bateman plays somewhere between chilly and vanilla, he’s the guy who would rather talk your ear off about municipal bonds than look for the easy scheme. So when Marty is called by his flashier partner to a client’s offices in the middle of the night, and finds cartel boss Del (Esai Morales) asking about a missing $5 million, you would expect Marty to fold like a deck chair. But the flip side of Marty’s reticence is his calculation; that allows him to watch several people get shot in the head and dumped into barrels of waste and then stay cool enough to concoct his last-ditch plan. After all, this is a man who was just as involved as his partner in laundering money for Del, he just wasn’t stupid enough to start skimming from the cartel.

READ MORE: 10 TV Shows To Watch In July

Marty is crucial to whether “Ozark” will work, and it’s one of this hit-and-miss series’ unalloyed successes. The show starts things off quick, piling everything it can on Marty’s shoulders. Over the course of the pilot episode, he first has to convince Del that he can get $8 million in restitution cash in 48 hours. Then he has to make Del believe Marty can move his family down to the Ozarks and within a week set up a new money-laundering operation in that “virgin territory,” free from the prying eyes of the various federal agencies in Chicago, which Del doesn’t like because it has “too many Mexicans.” On top of all that, Marty has to actually do it, regardless of what his wife Wendy (Laura Linney) and two children (Sofia Hublitz as the eye-rolling teen Charlotte and Skylar Gaertner as the younger and quieter Jonah) think about the idea.

The early episodes of “Ozark” are structured as crisp but slow-build rural noir. Its mood is surprisingly downbeat, using the same cool and bluish visual palette once it moves from Chicago’s skyscrapers to the wooded inlets and low-slung stripmalls of the Ozarks (areas around Atlanta filling in nicely enough for southern Missouri). Although the scripts draw a bright line right away around the change of cultural scenery, with jutting references to “tweakers” and “dotheads,” the showrunners resist the attraction of too-easy stereotyping. Even the welcome introduction of the Langmores, a fascinating clan of trailer-dwelling grifters who end up as both rivals and allies to Marty, somehow avoid the pull of redneck grotesquerie. This low-key approach is all the more remarkable when one considers that the show’s creators, Bill Dubuque and Mark Williams, had a hand in last year’s most ridiculous movie, the Ben Affleck autistic ninja warrior flick, “The Accountant“.

With its pared-down look, eerie music, and attention to mood and character, “Ozark” is the kind of noir we don’t see much of on TV or streaming these days. The story isn’t invested at first in the nuts-and-bolts of the crime narrative; though that doesn’t mean it’s above copping directly from Martin Scorsese’s usage of the Rolling Stones’ “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from “Casino“ for a “here’s how money laundering works” montage. More important is Marty’s constant weaving of new survival arguments, whether it’s trying to talk various small-business owners into taking him on as an angel investor or cajoling his family into adjusting to life in a place where “camouflage is a primary color.”

This is not a difficult character for Bateman to pull off, his post-“Arrested Development“ stock-in trade having been a long-suffering and exasperating moral rectitude, and something he’s clearly relishing playing (serving here as both executive producer and sometimes director). His narration that plays over the flash-forward opening, a litany of platitudes about the “American work ethic” and traits like “patience, frugality, sacrifice” are meant in part as ironic counterweight to watching him do murky deeds in the dark with a speedboat and some coolers. However, they’re also intended to be heard with utter sincerity. Marty is a crook, to be sure, but he’s a crook who wants to put in the hours. There may not be honor among thieves in Marty’s mind, but there is, or should be to his way of thinking, a work ethic.

That impatience with the quick and easy puts him at odds right away with his family, particularly Wendy, whose betrayal of Marty in the pilot episode nearly scuttles his plans right off the bat. But as the odd man out in a place that instantly distrusts everything from his big-city pushiness to his love of the Cubs, that ability to play the long game leaves both Marty and the show itself room to play all parties and possibilities against each other.

What “Ozark” could use more of is competent secondary characters to butt up against Marty’s ambitions; a few too many scenes pivot around his ability to out-think and out-talk the locals. To that end, the 19-year-old budding criminal genius Ruth Langmore (Julia Garner, further perfecting her stock role as a precocious teen who knows more than she lets on) who has her eye on Marty’s growing empire, and Peter Mullan’s ruthless backwoods kingpin will hopefully prove worthy foes. Marty’s too good a character to be left unchallenged. [B]