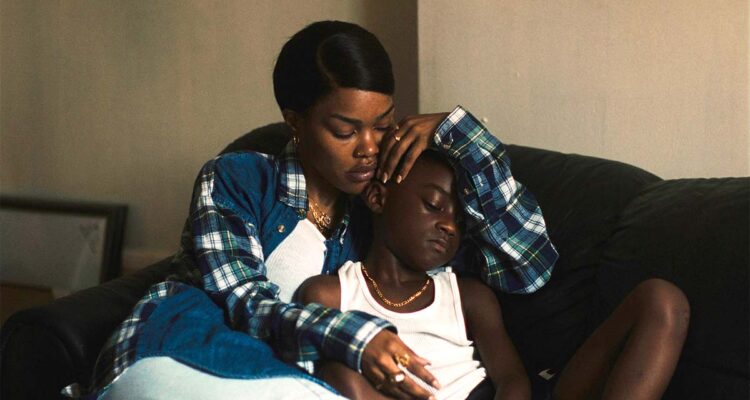

In writer/director A.V. Rockwell’s feature directorial debut, “A Thousand and One,” Inez (a deeply felt Teyana Talyor) has returned to Harlem after spending a year in Rikers Prison. The year is 1994, and Harlem is still bustling with its own unique flavor and culture, awash in hip-hop music, blue jeans, gold chains, and oversized coats. Inez, however, doesn’t have a place to stay. And more importantly, she doesn’t have her six-year-old son, Terry (Aaron Kingsley Adetola). When offered the chance, Inez illegally whisks Terry from his foster mother, gives him a new name, Daryl, and phony papers. It’s enough to start a new life but never enough to feel wholly safe.

READ MORE: 25 Most Anticipated Films At The Sundance Film Festival

That’s because their environment is perpetually under threat. See, “A Thousand and One” is as much a story of a city, specifically of Harlem, as it is about the people: Through Rockwell’s subtle eye, we witness how the storefronts of local business switch over to the corporate chains, how the demographics of the neighborhood slowly shifts from people of color to white, how condos rise as brownstones fall. Rockwell’s gentle hand on this subject causes one to wish we hewed closer to the narrative of the neighborhood and became more integrated into the peculiarities of the area (who are the smaller people, the tiny characters who make a neighborhood a neighborhood?).

Rockwell’s deft screenwriting lightly weaves the arc of Harlem with the rise of extralegal policing: The emergence of stop-and-frisk is mentioned, and the aggressive policies by former Mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg further shape the picture. These themes are felt more through place and setting than character beats, which gives us a sense of the passing eras but not as much information about Terry and Inez… or, really, anyone else in their orbit.

“A Thousand and One,” from Rockwell, a throwback family drama, is a handsomely shot story about Black kinship, the wild reach for seemingly faraway dreams, and the crushing blows delivered by a vicious white-led political system wanting to erase the historical Harlem.

It’s also long. Running at 116 minutes, the modestly operatic narrative initially surges on Gary Gunn’s sweeping score and Erik K Yue’s breathtaking photography, which uniquely wraps us in the warm glow of the 1990s. The film then lurches ahead: Inez’s boyfriend Lucky (Will Catlett), Terry’s father, returns from prison. The trio attempt to form a family, and in another movie, their journey in this period would morph into a feel-good story about overcoming adversity by loving one another. Life, unfortunately, isn’t so simple. Rockwell opts for a kind of realism that feels more truthful; and yet, is without a tight rhythm.

We leap forward from the 1990s to 2001 and then to 2005, following a similar structure as “Moonlight.” Terry grows into a young man nearing graduation from high school. An oncoming tragedy strains his relationship with his mother as their landlord uses nefarious methods to push them out of their Harlem apartment. Rockwell pulls her focus from Inez to Terry (Josiah Cross), which feels like a mistake, as despite Cross’ lived performance, Terry is too blank. He barely grows from the six-year-old kid we first met, which is partially the point. The void between him and Inez stunts his character. But Rockwell gestures toward the void rather than fully contextualizing it. The opaqueness robs “A Thousand and One” of a deeper, personal lens.

Instead, the narrative veers toward a melodramatic twist, which doesn’t as much put the system on trial but works for an emotional payoff that nearly feels unearned. If it weren’t for the deft performance by Taylor, delivering a heartbreaking monologue, which speaks to the sacrifices offered by Black women so Black men might find a better future, the sequence would crumble under the weighing artifice. But Taylor delivers such a palpable swing the potency of the intended pathos remains mostly intact. That is until the film’s all-too-neat final shot, which betrays Rockwell’s insistence on realism.

While “A Thousand and One” is a breathtakingly beautiful portrait of Black womanhood and is thoughtfully political, the character beats heave with a noticeable unevenness. The fascinating parts rarely add up to a satisfying interpersonal whole. Still, as a story of a time and place, as a narrative about how Harlem changed over time and how those brutal transformations affected the most vulnerable, Rockwell’s vision is commendable, if not relatively successful. [B-]

Follow along with all our coverage of the 2023 Sundance Film Festival.